It’s no secret that artificial intelligence has gripped the higher education sector in more ways than inside the classroom. Although most colleges and universities are scrambling to moderate precisely how students should be allowed to use it, faculty and administrators are inviting its use systemwide.

An EDUCAUSE poll that surveyed institutional leaders, technology professionals, and other campus stakeholders found that 67% are optimistic or very optimistic about using AI. The same proportion of respondents reported using a generative AI tool for their work, and another 13% anticipate using it in the near future. With eight out of 10 respondents embracing its use, AI is proving to be a dynamic tool with deep implications outside the academic sphere.

“I don’t think it does us any good to villainize these technologies, said Rebecca Sandidge, vice president for enrollment management at Oglethorpe University (Ga.). “If used appropriately, AI can do some of the things we pay college consultants to do.”

AI in the accreditation process

Every five or so years, colleges and universities must cull together a committee of campus stakeholders to create a weeks-long, painstaking self-report study that defends its allotment of federal funding to its institutional accreditor. The process requires several writers and a deep commitment of internal resources to complete correctly.

For Glenn Phillips, an account executive at Watermark and former director of assessment at Howard University, it’s no question that committees are using ChatGPT to help jumpstart the writing process.

“People are 100% using AI right now for accreditation writing,” he says. “I know several folks who have ChatGPT open on their browser at all times. They’re using it whether you want them to or not.”

Because most accreditors require their institutions’ reports to be narratively driven, some may argue that using ChatGPT, which Phillips concedes doesn’t create “compelling” writing, may undermine the spirit of the self-study. However, no accreditor has drawn a formal policy on its use yet. Nonetheless, Phillips believes the aid of the tool will only boost writers’ efficiency while keeping the integrity of the accreditation process intact.

“I think it adapts a new technology for efficiency and what is a largely thankless and often institutionally overwhelming and highly resourced activity,” he says. “I think that institutional accreditors would be wise to create policies that recognize the use of AI but do not create undue burden or restriction on authors regarding that use because there has been no evidence that this makes accreditation worse.”

Admissions

With admission offices nationwide plagued by high turnover, admission officers are turning to generative AI to help ease the workload and alleviate employee burnout. More than 80% of educational professionals (82%) with expert knowledge in their institution’s admission process say their admissions departments will use AI by 2024, according to Intelligent, a higher education planning resource for prospective students.

Among the respondents who use AI, 85% said it increases their efficiency, especially with reviewing transcripts and letters of recommendation. Machine-learning services like SIA purport to be able to scan hard copies of transcripts and extract exact courses, grades, and credits in seconds without error.

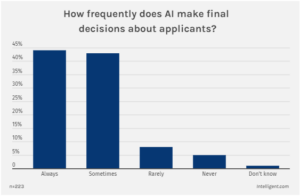

But beyond just using AI to help inform officers on their decision-making, 87% said AI ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ made the final decision on whether to admit students. Between the two responses, they shared a striking level of parity.

Diane Gayeski, professor of strategic communication at Ithaca College, believes admission officers’ interdependence on the technology can prove vital to helping correct judgment errors that derive from being inherently biased humans.

“Human decisions are not without bias, and AI tools might actually be used to combat systemic racism or ageism,” Gayeski continues.

Still, skepticism persists. Two of three professionals noted that they are concerned about AI’s ethical implications despite their heavy use of it.

“At present, the help that AI brings to our work is still very great. Whether it will have a negative effect in the future, we will have to see,” wrote one survey respondent.

Enrollment

In order to funnel student applications through the admissions process, institutions must ensure they are catching potential students’ desire to apply in the first place.

The University of North Texas and Reynolds Community College (Va.) are among a growing list of institutions buying into AI-powered predictive analytics and data visualization products to strategize more effective enrollment tactics.

One way North Texas is exciting potential students’ interests at the prospect of a degree from their university is by analyzing vast swaths of publicly available data on which academic programs students attempt to enroll in at their institution – and also of those at other competing colleges and universities. By analyzing which programs students are attracted to but aren’t properly supplied, North Texas can parse the data to identify high-growth areas for in-demand academic programs.

Reynolds uses the technology to increase its student retention and persistence rate, an essential ingredient of year-to-year student enrollment at colleges and universities. For example, the community college is conserving its limited well of student support resources across its 15 STEM subjects by gaining better insight into which courses students are struggling with specifically.

“This is the most data-informed [staff have] ever been in their entire lives,” said Melanie Boynton, director of institutional research and analytics at Reynolds.